I’ve not had good luck with mothers-in-law. Can’t blame ‘em, really. I certainly was a mother’s worst nightmare.

1.

It’s only from a half-century’s distance that I’m willing to imagine how awful it must’ve been for Ginny, nestled as she was in her mid-century middle American suburban box where the rules of behavior were strict, crisp and clear. They guided how to dress, how to speak, how to manage relationships with church, colleagues, friends, and neighbors. No ambiguity in the expectations. One wanted to stand out, of course, but only by excelling within the rules.

Three daughters, happily married (or so she believed) to solid, upstanding husbands. This was how things were supposed to be. Daughters she could brag about, their achievements were her achievements. Sandy was the eldest, married to Roger, a music teacher and high school band director. Instead of college, she’d followed her mother into retail, and at 26, in the late summer of 1975, she was a success. Her title at Prange’s, the elite department store in Appleton, the big city1 in the string of villages and towns that populated the Fox River Valley, was Fashion Coordinator. She was responsible for overseeing the buying of the high-end clothing lines, she managed special events, she’d done a little modeling, she was being groomed for an executive position.

In that same late summer, I was 19, bumming around the Valley with my best friend Kevin. My hair hung halfway down my back and I had a thin scraggle of a beard. I favored tight patched jeans, loose poet shirts, John Lennon glasses. I’d just finished my third semester at the University Extension in Fox Valley and would be going to UWM2 in the fall as a music composition major. Kevin would be going to Southwest Minnesota State, following his two year stint in the Navy. We made some half-hearted attempts at looking for jobs, but mostly we got stoned. He’d borrow his mother’s car and we’d drive around the Valley, me with my guitar, playing music in the parks, trying to entice girls. We were successful at that and by late June had found summer loves, to whom we stayed mostly faithful. The days were hot, the evenings were pleasant, warm breezes in the trees, crickets chirping. We’d pick up the girls and go looking for adventures. We’d go skinny dipping in Lake Winnebago, had a memorable acid trip one night when the foster family my girl lived with was out of town. I’d write songs, playing guitar while Kevin and I sang. It was our summer of sex, drugs, rock & roll. In small town Wisconsin, 1975 was still the Sixties.

In August, Kevin saw a casting call for a community theater production of Jesus Christ Superstar. We went. He was a fine actor and singer with a big personality, perfect for Judas. I was a guitar playing apostle. Sandy was Mary Magdalene. Roger was the band director.

The show was a hit and we revived it just a few months later, during Christmas break. It was during that run that Sandy and I often ended up in long late heartfelt conversations at the cast parties. I learned about her artistic aspirations, how she’d wanted to go to college to study art, but her Mother had insisted she have a sensible career and used her connections to get Sandy her first job in retail. How she’d felt free and unbound when she married Roger, but how it had all too soon turned into the drudgery life she longed to escape. I talked about philosophy and showed her my poems, told her about my fantasies of life as a singer/songwriter. Told her how my parents were supportive of whatever I chose to do, as long as I was making good use of my gifts. She was envious.

You’ve seen how it happens, over and over; how you find yourself in conversation with someone who seems so unlikely, but who understands you better than anyone ever has; how when you’re in conversation it’s as if a dome has descended, protecting the two of you from the intrusions of the rest of the world. They say the brain isn't capable of mature judgment until one's mid-20s. Surely for me it wasn't until at least my late 30s. Despite my outsized intellect and vast book learning, I was still so much of a child, rarely able to see past my own desires but a wizard at justifying them. After the show’s run I’d spend time with her when I came home from school occasional weekends. More long late heartfelt conversations and by March we were in bed together. By May she’d filed for divorce, moved into her own apartment and was making plans to quit her job and go to art school.

I don’t remember when I first met her parents. Nick was the ad manager for the local CBS affiliate. A small guy, light on his feet. Exuberant, a glad-handing kind of guy; relentlessly optimistic and upbeat. But also a bit of a Willy Loman vibe. On the downslope of his career, he’d never broken through to do national sales. It was a good career, but it was still just a local station in a small market, never quite what his dreams might’ve been set on. Maybe that made him more generous with a kid who was still nothing but dreams, having barely accomplished anything at all. He was willing to give me the benefit of the doubt, always looking at the bright side, always looking for the positive spin. We got along alright.

Ginny was another matter. Appearances mattered. Doing the right things in the right way. More than once, Sandy recounted her mother’s reaction when a high school friend became pregnant. “If you ever did that to me,” she’d said. “I’d never be able to face the neighbors.” In Sandy’s mind, that encapsulated her mother’s worldview. I can’t recall a single conversation I ever had with her. I just remember the iciness. I wasted no sympathy on her.

And then there was the wedding. It must’ve just about killed her. This is two years later. I’ve graduated from UWM with a degree in philosophy3 and no job prospects whatsoever. I imagine I’ll eventually make a living with my writing and my guitar. I figure I can get a factory job or some such in the meantime. I’ve moved from Milwaukee to Oshkosh to live with Sandy, who is now an art major at the local UW campus. She’s working at the Art Gallery there, so we decide that’ll be the wedding venue. We write our ceremony, snatches of sentimental poetry and vows to support each other’s artistic dreams. I curate the playlist4 and we talk the director of Superstar into being our officiant. We have no interest in a typical wedding reception. We want to party with our friends at our apartment. My parents agree to hold a family gathering at their house. The plan is that Sandy and I will spend some time there after the wedding hanging out with both families and then decamp back to our apartment for the real party.

This is too much for Ginny. She’s not going to be shunted off to her new in-laws, people she doesn’t know, who’ve allowed their son to become this vile creature who’s seduced her daughter and destroyed a perfectly good marriage. She insists on coming to our apartment. But of course our apartment is full of stoned twenty-somethings getting high and drunk while the music blares and there’s no way we’re letting her in. So the compromise is that we bring out lawn chairs and Sandy’s parents, sisters (with husbands and kids), aunt and uncle, camp out in our tiny patch of backyard for a couple of the most uncomfortable hours of my life.

Sandy and I were doing things our way and felt totally justified. I’d been living the hippie lifestyle since my mid-teens and in those two years Sandy had vividly rejected the conventions in which she’d been raised and which she’d spent her twenties trying to live by. Her involvement with me opened the door for her to fully break from the life she felt she’d been forced into. She’d eagerly embraced my stoner lifestyle, easily made friends with my friends. She’d take the bus down to visit me. In those first months I was still in the dorm and I’d have to sneak her into my room. That she’d show up with perfect makeup and hair, bright lipstick and a chic little overnight bag, looking completely unlike the students passing through the lobby of the dormitory towers made the notion of “sneaking” a joke. But the rules were loose and no one was screening who came in and out of the dorm any more than they paid attention to the wisps of smoke drifting from beneath the doors of any number of suites. You had to be really outrageous to get busted.

We believed we were artists, living the artist lifestyle. We had rejected conventionality. We were pure of heart, cosmic beings. We were appalled at Ginny’s refusal to accede to our wishes for our wedding. How dare she!

Things never got better, but her parents made the best of it. Nick’s unwavering sunny attitude and optimism enabled he and I to have a cordial enough relationship. Ginny insisted that we show up for our assigned holidays (alternating Christmases and Thanksgivings with my parents) and certain other family events. Over the next five years I started to morph into responsible guy. Cut my hair, trimmed my beard. Went to grad school. Became a librarian and got the prestigious fellowship at NLM. Wore a suit to work. But it was too little too late for Ginny and me. Once Sandy and I moved to DC, and then to St. Louis, we only saw them once or twice a year. The iciness never thawed. When the breakup came, a dozen years after the wedding, Nick and I had one long mournful talk. He didn’t exactly tell me I should stay and try to work it out, but the rules under which he lived dictated that he was supposed to try. Maybe Ginny was happy to have me out of her life forever, my abandonment of her daughter justifying what she’d always felt about me.

2.

Eighteen years after first horrifying Ginny, I was slightly less callow, but no better a match for the daughter of the Colonel and his wife. For many years, ever since her divorce from Ed, Lynn had said little to her parents about her personal life. So when I showed up with her after our camping trip at Pedernales Falls,5 she hadn’t given them much warning. We stopped along the drive so I could buy a nice short sleeved sport shirt, the kind responsible young men wore, the kind I didn’t own a single example of.6 It didn’t help.

They showed me to Bob’s den, where I’d be sleeping. Lynn would be back in her old bedroom and it went without saying that I would not be joining her there. The den was a shrine to Bob’s military career. Hanging from the ceiling were models of some of the aircraft he’d flown during the Korean and Vietnam wars.7 The walls were covered with award plaques and photos – here he is with Bob Hope, here he is with the governor of Arkansas. Here’s a display of his medals and ribbons, here a humorous citation from the men in his bomber squadron when he left for his next assignment. When I pulled back the covers on the small camp bed, the sheets were striped red, white and blue.

Since we weren’t entirely sure what the status of our relationship was, she couldn’t explain it to Bob and Marian.8 That I was the director of a library and in a weekend country punk band were not considered assets. A few days after our visit Lynn received a long letter, outlining the reasons for their disapproval. “Plays guitar in smoky bars” rings in memory. I suppose playing in smoke-free venues wouldn’t have improved my prospects much.

At the time, I was 38 and Lynn had just celebrated her 44th birthday. They worried that as a librarian (they had little idea what my job actually entailed) I wouldn’t be able to provide for Lynn in the manner to which she ought to be accustomed. Lynn was infuriated, but not surprised. She was vice-president of a global company and could provide for herself perfectly well. But ever since she’d left for college her parents, her mother in particular, couldn’t seem to grasp that she was capable of making her own decisions and finding her own way. Despite her professional success9 they seemed to long for her to eventually settle into some idealized version of a happy 1950s family. That was not going to happen.

I described our wedding in The Wabbit. Sufficient here to point out that it was, in its own way, nearly as unconventional as my first wedding had been. We knew enough to give Lynn’s Mom a role, and luck enabled us to have a marginally acceptable reception. Still, what stands out in memory is my Mom’s reporting that when she made a comment to Marian about how happy we looked, the response was a grim, “Sure, they look happy now...”

For the next thirteen years, Marian and I attempted to manage our mutual dislike. Visits were blessedly few. Lynn had long since made it clear she was not coming “home” for holidays. The increased stresses of divergent expectations of holiday responsibilities had invariably led to screaming matches. When we did go to see them in North Little Rock, or when they came to visit us in Birmingham, everyone stayed tense and on edge, waiting for the inevitable cutting remarks of disapproval. No matter what Lynn accomplished, it was never quite enough to meet her parents standards, and they always found a way to let her know.

They say that travel broadens the mind, makes us more aware of how many valid ways there are of living in the world, humbles us. Marian was an exemplar of the opposite tendency. She’d been around the world as an Air Force wife and after Bob’s second retirement10 they traveled widely, but the more she saw of the world, the more she disparaged it. Her world became smaller and smaller, the gap between “us” and “them” wider. An obsessive racism began to emerge that Lynn said had never been apparent when she was a kid. There was the time we were all out to lunch and “our” Marian – Lynn’s daughter11 – was along. Marian (senior) started making disparaging remarks about Black babies, how they all looked like little monkeys, and Marian (the younger) who’d recently been named godmother to one couldn’t stand it and angrily called her on it. A bold and courageous move on her part, and it so startled her grandmother that she shut up.12 Not so a few years later when Bob and Marian were visiting us and at dinner Marian started to go into a screed about the increasing crime from “the Blacks” in Little Rock. I stopped her and said, “I can’t have this kind of talk in our house.” She merely doubled down. I got up and started clearing the plates, started cleaning up in the kitchen. Then she was mortified. Came into the kitchen asking if she could help. “No. Get out. I don’t want you in here.” Lynn and I went for a walk. I wondered what would happen the next morning. Lynn said, “They’ll act like nothing happened.” She was right.

When Marian died in 2008, it was not unexpected. She’d had various ailments for several years, with increasingly erratic behavior. We were at a conference in Cody, Wyoming, caught an early flight to North Little Rock for the funeral. Lynn shed tears for what might have been. She’d been grieving the loss of her mother for many years.

3.

What am I to make of this? I’ve held myself blameless. Sandy and Lynn had difficult relationships with their mothers long before they met me. The battle lines had long since been drawn and there was no question which side I was on.

Should I have made different choices? Could I have?

Now, in memory, the way Sandy and I handled our wedding “reception” stings. At the time I was furious with Ginny. Now I can see what a horrorshow it must’ve been for her. Back then I had no interest in seeing things from her perspective. The man I am now thinks he would’ve had more empathy, tried to make compromises, would’ve tried to find a way to have a positive relationship with her, fruitless though the attempt would certainly have been. Does that mean I think the choices I made then were wrong? I’m struggling with that, but I don’t think so.

This essay, along with maybe half of those I’ve done since posting The Island nearly four years ago, is an episode in what I think of as The Memory Project. I’m trying to better understand how I came to be the person I am, living a life that makes me happy, that I can call successful. There’s so much to be grateful for, and plenty to be proud of, but I also find myself spending a lot of time – maybe too much – ruminating on my failures. All the times I didn’t live up to my image of the human I want to be. All the times my actions caused other people pain. But what difference does it make, all these years later? Sandy’s dead. Roger, too. Her parents passed years ago. If I thought I behaved badly, is there anybody left to apologize to?

And anyway, is it fair to second-guess twenty-two year old me from the perspective of the me who’s gone through two or three lifetimes since then? When I was sixteen and going through a romantic crisis (one of my many) I wrote a note in my journal, directed to my twenty-four year old self. “I know that when you look back on this, it probably won’t seem like such a big deal to you. But for me, right now, it is a very big deal. Don’t ever forget that.” I haven’t. When I call to mind any of those earlier versions of me I see the me I am now as a semi-transparent overlay blurring the edges of the me I was then. We correspond at certain points, but at others diverge wildly. No doubt there’s a resemblance, but how much is the same? It does me no good to speculate on what I might’ve done differently if I’d known then what I know now. I have to remember what it was like for me then – did I make the best choices that me could’ve made?

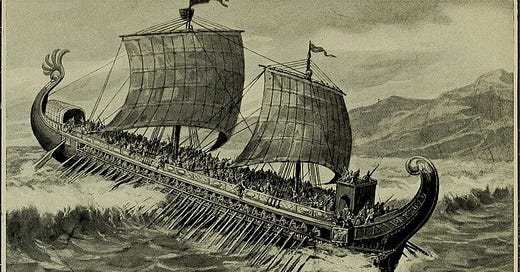

Up there, on that shelf of books from philosophy school fifty years ago, nestled among The Republic of Plato and Moral Problems and The Concept of Law and Logic as Philosophy and The Portable Nietzsche is a volume titled Personal Identity. It explores the question of how we decide that a thing is the same thing over time. The classic thought problem is the Ship of Theseus. In commemoration of Theseus slaying the Minotaur, the Athenians took his ship on an annual pilgrimage to Delos.13 Over time, as it underwent various repairs and refurbishments, there came a point where nothing material of the original ship remained. In what sense, then, was it still the same ship? And if it wasn’t, at what point did it change?14 What does it mean to say that I’m the same man now that I was then? Or am I someone different altogether?

Regrets. To say that I regret the consequences of some of my actions doesn’t always mean I wish I’d done things differently. But to say that I stand behind (most of) the choices I’ve made doesn’t mean I don’t regret the damage some of those choices have caused. Some of my choices were truly terrible, but what lingers alongside the shame of those few brutal bad decisions are so many little moments when I could’ve done better, been kinder, pushed harder against the fears and insecurities. Little things that wouldn’t have changed the overall arc of my life, but would’ve been better for those whose orbits brushed up against mine.

It's when I find myself in this loop that I wish/hope that reincarnation is a real thing. I want another shot! I know I can do better! All my life I’ve been told I’m an old soul. And I believe it. When I was a teenager I dreamed that meant I was a bodhisattva, delaying my own ascension into nirvana so that I could spend a lifetime helping others. More of my arrogance. Now it looks more like I’m a guy who just keeps getting returned because no matter how many lives I’ve lived I still haven’t managed to get it right. Sigh.

But back to the mothers-in-law. No, I don’t need to second guess the choices I made. It was the needs and desires of the daughters that mattered to me. Nothing I could’ve done in those days would’ve made my intrusion into their lives any easier for the moms to handle. Today I’m sympathetic to Ginny in a way I couldn’t be back then, but Sandy would’ve broken out at some point anyway, whether I was the agent of her liberation or not.15 With Marian, I was civil and polite, pushing back only when the racism became intolerable. We were never going to have a meeting of minds.

It’s okay that I’ll never stop sitting in judgment on myself. Tossing the what-ifs back and forth. All the should’ves and wished-I-hads. Isn’t that what personal growth is supposed to be about? That we learn from our failures and successes? That we resolve to do better? My divorce made me cautious about how I judge others. Each of us such a complex mix of competing values and desires, dreams and motivations. So much more than the slapdash labels that get thrown around on social media, where we sum up our enemies with a single word so that it’s easier to hate them. Live long enough and your multiple selves are a rollicking cascade of moments and identities, the best and the worst jumbled together. Small wonder Aristotle said you can’t judge a man’s life until after it ends. It’s hard enough for me to find the clarity to pass proper judgment on the sum of my own past actions; how can I have the arrogance to pass summary judgment on anybody else? May I at least have the humility to own all that I’ve done. All the selves I’ve been.

The Ship of Theseus. Every bit of me remolded, replaced, hammered and burnished and torn and re-sewn. Time and experience. All the ways I’ve flown and stumbled. This part gleams and glistens, over here I’m threadbare and worn. Everything different but somehow still the same guy. Sails up! Oars in the water! Delos on the horizon.

Population 54,000

University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee

A generalist by nature, I realized after a semester that I wasn’t willing to devote myself exclusively to classical composition in the way that success in that field would’ve required. That choice would’ve narrowed my universe. Philosophy and literature burst it open.

There’s a good chance that the cassette is somewhere in my closet. I know we opened with Ralph Towner’s “Icarus”. Dylan’s “Forever Young” was probably on there. “Follow You, Follow Me” from Genesis. You get the drift.

Detailed in The Armadillo Ate My Breakfast.

I wore dress shirts and ties, suits and sport coats at work, t-shirts and denim work shirts otherwise.

In the sixties he was commander of the base on Guam from which the bombers flew on their raids over Vietnam and Cambodia. That’s where Lynn went to High School.

Prior to the ultimatum in San Antonio, Lynn had been balancing the affections of me and the guy she’d been in a long-distance relationship with. When she finally agreed to choose me over him, just days before our visit to her parents, I’d been quite clear about my belief that we ought to be married, but she wouldn’t officially acquiesce until my formal proposal on St. Patrick’s Day a year later. At the time of this visit, she still thought my dreams of marriage were an unrealistic fantasy.

About which, we learned much later, her father often bragged to his friends, while rarely offering unadulterated praise to his daughter.

After leaving the Air Force he had a second career with the Arkansas IRS.

Yes, Lynn named her only daughter after her Mom. If it was intended to make them close, it didn’t work.

And apparently never forgot it. Marian was moved to “least favored grandchild” status. Her grandmother kept paper bags in the upstairs closets with the grandkids names on them that she would put discards in – things she was replacing that she thought the kids might be able to use. On one visit, Marian found the bag with her name on it. Eagerly she looked inside, but there was only a used garlic press. On another visit, she mentioned that a decorative antique baby buggy in the dining room was something that’d look nice at her house one day. By the end of the weekend, Marian senior had sold it to a neighbor down the street. Marian herself thinks she was doomed from the time she spilled milk on an antique rug when she was three.

Birthplace of Apollo

The Greeks loved these paradoxes. Zeno’s arrow – If you shoot an arrow, it has to travel half the distance before it reaches the target. It then has to travel half of the remaining distance, and so on. How, then, does it ever reach the target? In my late teens these thought experiments dazzled me. I still think they’re pretty cool. Athenian Zen.

Notwithstanding the very bitter, angry, and explosive collapse of our marriage, Sandy continued to thrive as the artist she wanted to be and attained some local success before she died of cancer at the all too early age of 56. By then it’d been well over a decade since we’d been in touch.

Thanks for sharing your story.